A Dancer’s Life: Meet Mollie Fennell Numark, Part I

Born in England at the onset of The Great Depression, Mollie Fennell Numark embarked upon a dancer’s life under unlikely circumstances. Shaped by experiences from a world faced with vast uncertainty, her disciplined career brought her from the great stages of England to the most renowned American nightclubs of the mid-20th century. Mollie remembers her emersion into theatre and the artform’s perseverance to entertain despite wartime dangers, and coming to the United States with the hopes and dreams that a country in peacetime promised.

Mollie Fennell Numark: During the year of 1939 my sister and I were very young and were hearing adults talking about a war. We lived in England. Europe and America had been living through an economic depression since the Stock Market crash in New York on October 1929. The 1930s dawned with the bleak reality of the Great Depression. Neville Chamberlain was the Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1937-1940. His name is associated with the policy “Appeasement” toward Germany. In the years before the World War II, he tried to detach Italy from Germany with an Anglo-Italian agreement of April 16th, 1938. The Munich agreement from September 30th, conceded Hitler all of his demands and left Czechoslovakia defenseless. Chamberlain returned a hero after his visits with Hitler, quoting, “Peace in our time”. During this period, we would hear Mum and Dad say “the war is on”, “the war is off”. We were thinking it was some sort of game they were all playing.

Black & white print: Fennell family portrait, left to right, George, Mollie, Pat and Sibyl, Blackpool, England, circa early 1940s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

When Hitler seized the rest of Czechoslovakia on March 15th, 1939, the appeasement was over. The Germans attacked Poland on the 1st of September. Our fateful day arrived on September 3rd, 1939, when Great Britain declared war on Germany.

Photochrome postcard: Blackpool Tower, Blackpool England, circa 1940s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws.

As soon as Dad heard the news, he asked Mum for any available money we had in the house. I had to empty my savings box. He took the collection and bought canned food at the store across the street. I’m sure it wasn’t very much, but we appreciated his quick thinking in anticipation of further hard times ahead.

It seemed that overnight the local factories turned into making munitions. Workers in certain jobs were put into these factories including Dad. He went to the one in the next street where we used to buy lollipops when it was a sweet factory.

Every house was instructed to tape up all windows as a precaution against broken glass. Curtains and drapes had to be made of black material and hung in every window. The whole country went into a blackout for the next 6 years. Street lights were kept off. Every night wardens would patrol the streets and yell, “Put that light out!” if they saw a chink of light anywhere.

My hometown was Blackpool, in Lancashire county in North West England. It’s famous Blackpool Tower was built in 1854 and remains to this day. Inside the Tower is a classic Ballroom and a Circus with all Victorian architecture, as well as an Aquarium, Aviary and Menagerie. The Zoo and Aviary were regarded as one of the finest collections in the country for some time, and included lions, tigers, and monkeys. The music heard from the Tower ballroom came from a Wurlitzer, and it’s been playing for many, many years. An amazing instrument. It sounds like an orchestra. The Tower became a significant part of my youth and influenced the course my life took.

Black & white print: Mollie Fennell, Blackpool, England, circa late 1930s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

As a child, I was sick for two years, which made me a physical wreck. At about five or six years old, my long illness of ear troubles began. It started with an ear ache, and antibiotics didn’t exist. I developed a mastoid and needed an operation behind the ear. The bone had to be removed. It was a very dangerous procedure because of it being close to the brain. The whole period is a blur of pain. During those couple of years, I was in and out of the Victoria, and Infectious Disease Hospital. The operations were a nightmare, fighting the ether mask as it was put over my face and going under with a terrible noise pounding in my ear. I wasn’t even able to attend school. I was also a little knock-kneed and pigeon-toed as a kid. If we were off for a walk, my mother would walk behind me, yelling, “Mollie, turn your feet out,” and I’d walk smack into a lamppost. In response to this problem, my mother enrolled me into the Theatre Arts School in Blackpool, which taught the Royal Academy of Dance and ISTD theatre [Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing].

Not long after starting at the school, a ballet teacher told me that I should start walking on the outsides of my feet to strengthen them. My sister said I looked like a penguin gone wrong. While learning to dance at the Theatre Arts School, World War II was in full force in the United Kingdom. One of the many horrific aspects of the war included the Blitz, which was a strategic aerial bombing campaign designed by the Germans to attack and destroy industrial cities in England during 1940 and 1941. Even after 1941, I remember carrying gas masks in a box to our dance lessons.

The Tower Ballroom, a Victorian style venue, is where I started my dance career. Today, it’s the international venue for ballroom dancing competitions throughout the whole of Europe. And the music, you see the white instruments in the middle on the stage, that’s the Wurlitzer, where you heard that music. And there are two little doors on side of the stage, we would come out from those doors onto the dance floor.

Photochrome postcard: The Tower Ballroom, Blackpool, England, postcard dated 2003. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws.

After years of taking ballet and tap exams [at the Theater Arts School], I was asked by the director, Annette Schultz, if I would like to be in the Tower Children’s Ballet. You had to be twelve years old, and the show consisted of a hundred children from twelve to maybe fourteen. That was the tradition there for many decades which began in the early 1900s. We rehearsed in the Zoo area of the Tower. Miss Schultz used to scream at everybody, usually me. If you couldn’t get a step immediately, she’d always yell at somebody. She’d be screaming and the lions would be roaring trying to drown her out. That was what our rehearsals were like. It was pretty traumatic.

Paper program page: The Blackpool Tower Circus program, advertisement for The Blackpool Tower entertainment, Blackpool England, mid-1940s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

In 1942 I was twelve years old, and it was my first show for the Children’s Ballet in the Tower. The traditional Christmas show was Jingle Bells, and it involved lots of dancing toys. My week’s pay was seven shillings and sixpence in an envelope. It was given to Mum and out of that amount I was given bus fare and on matinee days, money for a meal between shows. The only meal we could afford with rationing was beans on toast, mushrooms on toast, chips on toast, or peas and chips with a cup of tea. Dancers were always hungry.

Salute to Happiness was my first summer show. One scene was a beautiful white ballet to Chopin’s Minute Waltz. There was a little girl in the company who could play classical music, and there was a beautiful white piano on the ballroom floor. We were all dressed in gorgeous white tutus. We’re halfway through the performance and my frilly knickers, attached to my tutu came undone and started to slide down my legs. Well, try to do classical ballet with your knickers sliding down, it’s a little difficult, so I practically had my knees together trying to keep them up. And finally, they fell to the floor at the end of the music, so I stepped outside, picked them up and went off the stage, ran up the stairs and Miss Schultz grabbed me – and I thought I was a dead dancer.

These productions were staged as war raged on and we all faced daily reminders of its lurking danger. Sirens would go off nearly every night. That dreaded wailing sound gives me shivers even today when it’s used by the fire departments. When the nearby towns were being bombed, we would sleep under the staircase. We could always recognize the German planes flying overhead by their chugging sound if they were being chased after a raid. A street close our my house was bombed, as well as the local railway. People died. We played in the rubble later.

It was a challenge to be out at night with the continued blackouts. It was almost like having your eyes closed. Our town took in 2000 evacuees. All along our beach front in my hometown, steel poles were driven into the sand every few yards and put there to prevent ships from landing on our beaches. Gone were the donkey rides on the sands, the Punch-and-Judy show, the ice cream, and shrimp vendors. All street and direction signs were taken down throughout Britain in case we were invaded so the enemy wouldn’t know their way around. Neither did we.

Concrete barriers were built along the promenade. Air raid shelters were built in many streets and in the school yards. We were assigned to one in the next street, Selbourne Road where our neighbors the Crook family lived. During World War I, the Germans had used gas and the allies were afraid it might be used again, so everyone in each family had gas masks. The children’s masks were in the shape of Mickey Mouse in little square boxes with string attached to wear around the neck when leaving a building. During school hours we would have practice drills to try breathing in them. Dad found this very useful when pickling onions.

Paper ration book cover: Example of ration booklets distributed by the British Ministry of Food during World War II. Source Google image search. Image subject to copyright laws.

By 1944 the blackouts continued, and we were still on ration books. Ration books were small booklets given to everyone during and after wartime for shopkeepers to log individual purchases. This was done in order to ration certain foods and clothing that were scarce during the war years. Food items such as dairy products, meats and other goods were limited. Each person or family was only allowed so many of these products during a set period of time.

We were grateful that the air raids had ended. Unfortunately, the buzz bombs, also knowns as Vengeance Weapon Attacks were striking England. The German born engineer, Wernher von Braun, was the orchestrator of those V-2 rockets – buzz bombs (He would later develop rocket and space technology for the United States after surrendering to the Americans).

Churchill’s famous speeches from the underground War Rooms in Whitehall gave the people courage. STAY CALM AND CARRY ON. And so we did

The following winter the show was Christmas Cracker. The local paper review wrote, “A Christmas Cracker burst in The Tower Ballroom on Saturday afternoon and showered a hundred children into a forty minute cascade of song and dance.” The finale was the arrival of Father Christmas in a sleigh drawn by reindeer dancers. Myself and a group of other girls dressed in blue skating costumes danced a ballet on roller skates. We were chosen because we could skate, having spent years roller skating up and down pavements in our home neighborhoods. After falling on our butts and knees many times we mastered the art. Once we heard the applause, we forgot the pain.

Spring 1945 finally arrived. The war was over in Europe and Britain. May 8th, 1945 was VE Day [Victory in Europe Day]. Germany was defeated. Dad took us out for dinner on the promenade. We were still on rations, and we probably ate beans on toast. No more blackout. Britain turned on the lights and Blackpool could have the famous Illuminations along the promenade and our munition workers left.

The last show I ever did at the Blackpool Tower signified the end of the war. The Tower summer show was called Over the Rainbow. Beneath the bells of peace, we danced our way through thunder, lightning, wind, and rain and into sunshine and a rainbow. We ended with The Sunny Side of the Street. The theme of the show was heartwarming and appropriate to celebrate the end of the war in Europe. September 2nd, 1945 the war in the Pacific was over and it was time for the world to recover from the horrors.

Colorized photographic print: Mollie Fennell in costume, the Children’s Ballet, Over the Rainbow production, Blackpool Tower, Blackpool, England, 1943. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

The costume pictured on the left here was for Over the Rainbow. I was a French girl dressed in red, white and blue and danced with other girls to Mademoiselle from Armentières. And the finale of that production was a salute to the Royal Navy.

The Pageant of Thanksgiving and Remembrance was in The Opera House with military dignitaries and armed forces in attendance. I was thrilled to be asked to represent Russia as one of the allies. My costume was magnificent, black and red with the Russian emblem on the front of the gown. A huge memorial was center stage and other girls from my ballet school were also dressed as the allies. There were regiments of British forces, choirs and prominent politicians. And that was my last show there. It was a tribute to the war and all the people who died as a result. It was a sad remembrance, but also beautiful.

Miss Schultz asked Mum if she would allow me to audition for the summer show at The Opera House. I couldn’t believe I could be in a number one show. Dad sat me down for a serious talk. He asked if I wanted to continue my education or leave school for show business. I didn’t have to think of the option. “Dad, I promise to work hard and keep studying dance if you will let me try for the show.” He wished me good luck.

I finished the Children’s Ballet at fourteen. The Opera House Theatre in Blackpool was part of another entertainment complex that included Winter Gardens. It’s a famous opera house, and Tom Arnold’s 1946 revue Starry Way, was my first show there. George Formby was the famous British comedian from stage and movies and was known for his ukulele and comedy songs. Joseph Locke the Irish tenor, opera star May Devitt and Mexican movie star Movita were also on the bill. Movita had survived a bombing of a row of houses when visiting a friend and awoke one morning to find an article in a newspaper saying she had survived.

The opening number was Stairway of Gold, which involved a staircase that slowly came down from the back of the stage. All of us girls were dressed in gold sequined military costumes with high plumed hats. For weeks we practiced with silver maces, which we learned to spin walking down a gigantic staircase slowly lowered from a flat wall onto the stage. We came down row after row, after row with those batons. Three other girls and I were chosen to be in the front of the wall at the beginning of the number. Then the three of us would exit and run backstage to climb the back steps and make our entrance with a line of girls and descend the staircase. One night, we just walked off the stage and it came down with a smack. It was so frightening. The poor man that was operating it, all his ribs were broken, and he had to go to the hospital. The stagehands pulled it back up again, and we ran around, and came down the staircase, smiling like nothing ever happened.

One number I can still remember was named Hot Chocolate. We had to jump out of a cup of hot chocolate and slide down a slide trying not to land on our bums. Joan Davies was the choreographer. An American dance act, The Hightowers were amazing. Robert Hightower, an ex-Broadway dancer had been a fighter pilot during the war and was shot down by the Japanese. He had stomach wounds, four broken ribs, a cracked skull and multiple injuries to his neck and arms. Doctors in America didn’t think he would live. With a silver plate in his head and a steel belt to protect his muscles, he was now dancing with his sister Marilyn to applauding audiences. Robert Hightower was what show people call, “a real trouper”.

One performance during the Venice scene, Joseph Locke was singing to the opera singer who was on a scenery balcony. We were dressing the scene when the balcony started to sway forward, he didn’t miss a note. Our mouths were ready to scream when some bright stagehand managed to pull the balcony back.

Blackpool had a hospital fundraiser every summer. All the shows were in the parade with parts of scenery on trucks and all the cast in costume. We would hold out containers and people would toss coins for the hospitals. I was thrilled to be in the event remembering how the hospitals had saved my life.

Miss Schultz told Mum I needed to be a full-time dance student. Mum said she couldn’t afford to pay the tuition. Miss Schultz offered to cover half the tuition if I would help with the younger classes. Before my Saturday classes I would help the dance teachers with the little ones.

I wanted to go with some of our dancers to other cities in a pantomime for the Christmas season. Dad said I couldn’t go until I passed The Elementary Ballet Exam, which is a membership exam for The Royal Academy of Dance. I took classes daily to be strong enough to take the exam. To my disappointment when it was time, Miss Schultz said I wasn’t ready. I was devastated. I think she was afraid I’d leave her. I didn’t take the exam until I was in the USA in 1972.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Mollie Fennell and cast, Red Riding Hood pantomime production, The Opera House Theatre, Blackpool, England, circa mid-1940s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

The next show at The Opera House was a pantomime. The pantomime shows were always around Christmas, and they were always a fairy tale adapted into a production. This one was Red Riding Hood. The stars were Joseph Locke, Sandy Powell and Beryl Reid. The choreographer asked for volunteers to do flying ballet. The British company called Kirby’s Flying Ballet was the same system used in Peter Pan. Us dancers were promised an extra ten shillings if we learned to fly. I put my hand up immediately. For this, you’d wear a harness with the wires behind you, and you have the Kirby men backstage pulling them. We’d fly across the stage as mystical figures over the ballet below. In rehearsals you would get dropped a few times but, you have to carry on.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Mollie Fennell (center back) and other dancers, Blackpool Tower Circus, Blackpool England, circa 1940s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright. Please do not appropriate.

The following summer Miss Schultz booked us in the Tower Circus as the Circusettes. The circus that first opened in 1884, was a hippodrome style stage ring. The one-ring circus within the Tower is an amazing thing. During any production’s finale, the ring lowers and is filled with water, and a water spectacular unfolds. There was a distinct finish for every show. We rehearsed a roller skating ballet, which was more difficult than the one we did in the Children’s Ballet. Our costumes were blue satin with white roller boots. Every show started with a parade, and I was thrilled to lead some of the ponies into the ring. Of course, doing ballet in roller skates, it’s a little different experience. We fell down a lot, but as always, when you heard the applause, you’d forget the pain. It was lots of fun.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Mollie Fennell (left) and fellow dancer in costume, Every Time You Laugh, Winter Gardens, Blackpool England, circa mid-1940s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

My first show away from home was in Manchester at the Palace Theatre. It was a pantomime. The tradition of the pantomime is that the male role is played by a female and the comedy Dame a man’s role. We did an adaptation of Babes in the Woods based on the story of Robin Hood, and again I was flying. I remember our digs. The landlady didn’t know how to cook.

The next summer show was in 1947. I was booked at the Winter Gardens performing in Every Time You Laugh, starring Dave Morris, Nat Jackley and Joseph Locke. Produced by Robert Nesbitt. This time we had to learn to play castanets for The Lady of Spain number, which opened the second half of the show. It was fantastic and we were dressed in black lace Spanish gowns. One night, the singers were singing, and everything was happening as usual. The theatre had a fire curtain that came down at intermissions. One night after intermission, the fire curtain stuck and wouldn’t raise. The orchestra leader started and we were all standing backstage talking to each other and forgetting what we’re supposed to do. Suddenly up went the fire curtain, and we’re all still standing around talking to each other. The orchestra leader did not stop and start from the beginning again, so we had no idea where we were at in the music. The castanets are going and everybody’s singing in the wrong place. We all started to laugh.

Between rehearsals and performances, we would go to a café, The Palm Court for food. All the dancers from The Opera House, Winter Gardens and the London Tiller Girls would meet. The London girls wouldn’t have anything to do with us Northern girls. They were snobs except one Tiller Girl who would sit with me and chat. Her parents were Scots so that made a difference. Her name was Irene Manning, and she was a beautiful brunette, and we were friends forever.

Summertime I returned to the circus. In the water finale before the ring would lower and flood with water and fountains, I had to climb a ladder onto a huge whale and hold the reins as if it was swimming in water. Some of the girls appeared in large scallop shells while other girls swam in a water ballet. One performance I was walking by the polar bear cages and a bear grabbed my arm. A trainer managed to get the bear to let go of my arm. No harm done, I felt sorry for the bear in a cage.

In 1948 I was in a pantomime in Liverpool. It was Cinderella. I was to share digs with a girl named Monica, whose parents later in life sponsored my family to move to America. In the aftermath of the war, Liverpool streets were still piled with rubble from the Blitz. It was so bad in Liverpool, it was practically destroyed. We’d climb over the rubble with our ration books to get some food and take it to our landlady. Our digs had a broken window, and this is the dead of winter, stuffed in with a piece of cardboard and covered by moldy blinds. It was awful.

Cinderella with George Formby and his wife Beryl was a lavish show with ponies pulling the golden coach and I was in the flying ballet again. This time I had to spin from the stage up to the flys and somersault across the stage. One night my wires got caught on the scenery before I was supposed to land. Back and forth I flew across the stage yelling in the wings, “Get me down!” The orchestra kept playing the same piece of music and the audience followed me as if at a tennis match. The finale was the wedding scene, and we were Cinderella’s attendants.

We used to have Christmas Day off so we would catch the last train Christmas Eve to go home for the day. Most times we had to sleep on the floor of the train because the Army had all the seats.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Dance line, Mollie Fennell third in from right, Blackpool Tower Circus, Blackpool, England, 1948. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

For the Summer of 1948, I returned to The Tower Circus as one of the Circusettes again. Our director, Miss Schultz, always had brilliant ideas. One particular season, she put the small girls on trapezes and bareback horses, jumping on and off, doing ballet on the horses. I was grateful that I was too tall. Then she decided all the tall girls were going to learn to juggle. We started by learning to juggle with three hoops. The hoops would cut us between the thumb and the finger, and we bled all over the place. Finally, we said, “We can’t do this. This is awful. We’re bleeding to death.” It took a long while to persuade the director that we were not going to do this. In response, she ordered some new ones which were smooth, so we were able to use them. We continued to rehearse for weeks learning how to juggle. And it was all done in precision, and we’d have to throw a hoop to the girls, and they’d throw them back, and it was quite amazing once we perfected it.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Dancers performing, Blackpool Tower Circus, Blackpool, England, 1948. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

In the circus I was asked to be a part of the famous clown Charlie Cairoli’s act. I had to be in a large box and wear a boxing glove and hit Charlie through an opening in the box. At the end, the box would open and I would parade across the circus ring. No extra pay, but at the end of the summer, Charlie gave me a five pound note and a bottle of perfume.

Left: Paper program cover featuring Charlie Cairoli. Right: Black & white gelatin silver print, Mollie Fennell in costume, Blackpool Tower Circus, Blackpool England, 1949. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Images subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

In the water finale we looked like creatures from outer space because we were covered with silver sparkles over our skin and even our faces. We were listed as The Crystal Girls while the Colberg Christal Wonders performed their amazing acrobatics. It was hard to remove the silver sparkles at home with one bathroom and multiple boarders in the house.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Water finale, Blackpool Tower Circus, Blackpool, England, circa late 1940s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

The Circusettes and many performers from the Blackpool season were invited to perform in The Royal Command performance for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth at The London Palladium in November of 1948. This was thrilling because if you’re in show business in England that’s the top of the line. New costumes were made of pale blue satin.

Julie Andrews was there with her little pig tails. She was just thirteen at the time and was part of the performance. Danny Kaye was the headliner. Our digs in London were at the Theatrical Girls Home in Soho, which was the middle of the prostitute area. The home was run by an order of nuns. I think they ran it to keep us from “The Wicked Life Upon the Stage” [A song from Showboat]. The building was full of tiny little rooms with big crosses over the beds. The nuns were all in black with lots of chains and keys around their waists. And if you wanted a bath, they would come in and measure it with a measuring stick. We were only allowed two inches of water. We had to get food from the little hutch by the kitchen, it was like Oliver Twist, “Please, may I have some more?” That was really what it was like. The rehearsals, however, were in the Palladium. Danny Kaye was always nice. He would often come and talk to us.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Circusettes, Mollie Fennell third from right kneeling, Royal Command Performance, London, England, 1948. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

The Palladium had official Royal Box seats for the royals where the King and Queen, Princess Margaret and Duke of Edinburgh watched the performances. Princess Elizabeth was home because she was pregnant. The performers were told not to look at the Royal Box. It was a big ‘no-no’. The big night arrived. We were so nervous opening the performance and worried about dropping a hoop. The curtain opened and we were almost blinded with the jewels in the audience. We didn’t drop one hoop. The applause is a wonderful memory. For the finale, everyone was on stage. I said to myself, “If I don’t take a peek at the Royal Box, I’ll never have another chance.” I turned and looked up at the box. The show finished with There’s No Business Like Show Business followed by the national anthem. The next day the newspaper published a finale photo with two heads turned to the Royal Box. Danny Kaye and me. I was terrified someone would notice and I’d be in trouble, but nothing happened.

Newspaper clipping: Cast takes the stage at Royal performance, London Palladium, London, England, 1948. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws.

We took the train back to Blackpool where we were booked into The Palace Theatre to perform our Royal Command performance for a week starting the following day. At the end of that week, I asked, “Aren’t we getting our paycheck?” I was told, “It’s an honor.” I replied, “But I have to get paid. I help my mother at home. I need to get paid.” “No, it’s an honor. It’s an honor.” So, I found out about the British Actors’ Equity. I signed up with some other girls and we got paid.

In 1950, I was at the Winter Gardens production, Take It From Here with the stars of the radio hit show, Jimmy Edwards, Joy Nichols, and Dick Bentley. Produced by George and Alfred Black and Jack Hylton. We were billed as Annette’s 16 Dancettes. The John Tiller Girls were in the Opera House show. Irene (my friend from the Tiller Girls) and I would meet for a cuppa in The Palm Court and continued our friendship.

Paper program cover: Take it From Here production program, Winter Gardens, Blackpool, England, 1950. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

I was given a dance partner in this show for the first time. He was six feet tall, and we’d have to do lifts. I had to do one lift where I’d spring from a sitting position on the floor onto his shoulder. He’d pulled me up, I’d hit him – boom, on the floor. We tried it quite a few times, but he could never do it. We eventually had to change the lift. The show ran through the whole summer season. It was then sent to the Adelphi Theatre at The Strand in London. So, I found myself back in London again.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Dancers, Mollie Fennell third in from right, Take it From Here production, Winter Gardens, Blackpool, England, 1950. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

There was a beautiful white ballet with my six foot partner. We also did a precision tap routine. A new number was added to the show from High Button Shoes, It was the scene originally inspired by silent era slapstick films of Mack Sennett. It was a riot, we laughed all through rehearsals. My role was Mama Crook. I had a green face, black wig and long green fingernails. After all the work the show was too long, and the number was removed. Harry Dawson was our lead singer and sometimes I’d take his lovely daughter for a walk in a park. Her name was Lesley, and I named my first child after her.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Dancers, Mollie Fennell & partner standing left, Take it From Here production, Winter Gardens, Blackpool, England, 1950. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

The show was mostly done barefoot, which was another painful experience because I had a problem on the sole of my right foot. In one scene, which was a Native American dance, we had to leap off a ramp with spears. I was sent to a foot doctor for a few weeks. Another number we had to perform knee slides across the stage. One day during a high kick I pulled some muscles and was sent to a hospital for therapy. The theatre paid the bills. No day off because we still had to work.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Scene from Take it From Here production, Winter Gardens, Blackpool, England, 1950. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

Our digs were in the town of Barns over the Hammersmith Bridge. Our hosts were people who rented out their homes to theatricals, and this time we had a giant and seventh dwarves, and one bathroom. So, you can imagine the queue, trying to get by a giant and all these dwarfs. And you had to light your own heater to get some water. One time I lit it incorrectly and it blew out the window, so I lost all my week’s pay in the wind that morning.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Scene from Take It From Here production, Mollie Fennell back far right (upside down), Winter Gardens, Blackpool, England, 1950. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

On our day off friends and I would become tourists. Some of my favorite trips were the Thames boat ride to Hampton Court, The Tower of London, and Westminster Abbey. I finally talked Mum into coming to London for a few days to see the show and the sights in London. It was her first visit to London, and we had a memorable time.

I returned to Blackpool after that to audition for The John Tiller group and landed a contract for the City of Oxford. Aladdin was the pantomime. Oxford was beautiful. I loved watching all the guys on their bicycles in their robes, bicycling away to the university. I was assistant to the choreographer for this show and I had a minor speaking role as Hi Ki. I danced in all the numbers too. After the choreographer left, I ran the weekly rehearsals and took notes.

Black & white gelatin silver print: Scene from Aladdin production, Mollie Fennell as “HI KI”, far left, The John Tiller Girls, Oxford Theatre, Oxford, England, early 1950s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

During that production, the principal dancer, Betty, and I became friends. She asked instead of staying in the digs if I would like to stay at her home in Henley, which was beautiful, and by the Thames River. She had a little old car she called Lizzie. Every day we’d go back and forth from Henley-on-Thames to the Oxford Theatre. There was no heater in the car, so we used a blanket. One day Lizzie decided to break down. Now, you can never be late for the theatre, you just can’t, so we hitchhiked. Somebody rolled along with a car, and two men got out and we explained our problem. “Oh yes, we’ll take you to the theater,” they said, “No problem.” They took us to the theatre, dropped us off, everything was fine. Intermission, the police came in, the two men had just escaped from prison and they went back to try and fix the car as another getaway car. The two of us wound up at the Old Bailey. The Old Bailey is the most famous courthouse in Britain. It was intimidating being there. Even if you’re innocent, you feel guilty because the Barristers are there with the white wigs, and it’s very scary. For two days we had to be there, two whole days, back and forth. Finally, the men were convicted and were returned to jail. My friend got her old car Lizzie back. I haven’t hitchhiked since.

My Last Show in England was London Laughs at the Adelphi Theatre. The famous Vera Lynn was the star of the show. She was the best known during the war years for keeping British spirits alive. Her radio show, Sincerely Yours, helped bridge the gap between fighting soldiers and their families. This was the first time I did a real kick line and the first time I rehearsed I wrenched my ankle. My friend and fellow Tiller Girl, Irene, helped me down the stairs and met me the next morning to help me up again. I knew I had found a true friend. I was very proud to be a John Tiller Girl.

Paper program cover & page: London Laughs production, the John Tiller Girls, Adelphi Theatre, London, England, circa early 1950s. Courtesy Mollie Fennell Numark. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

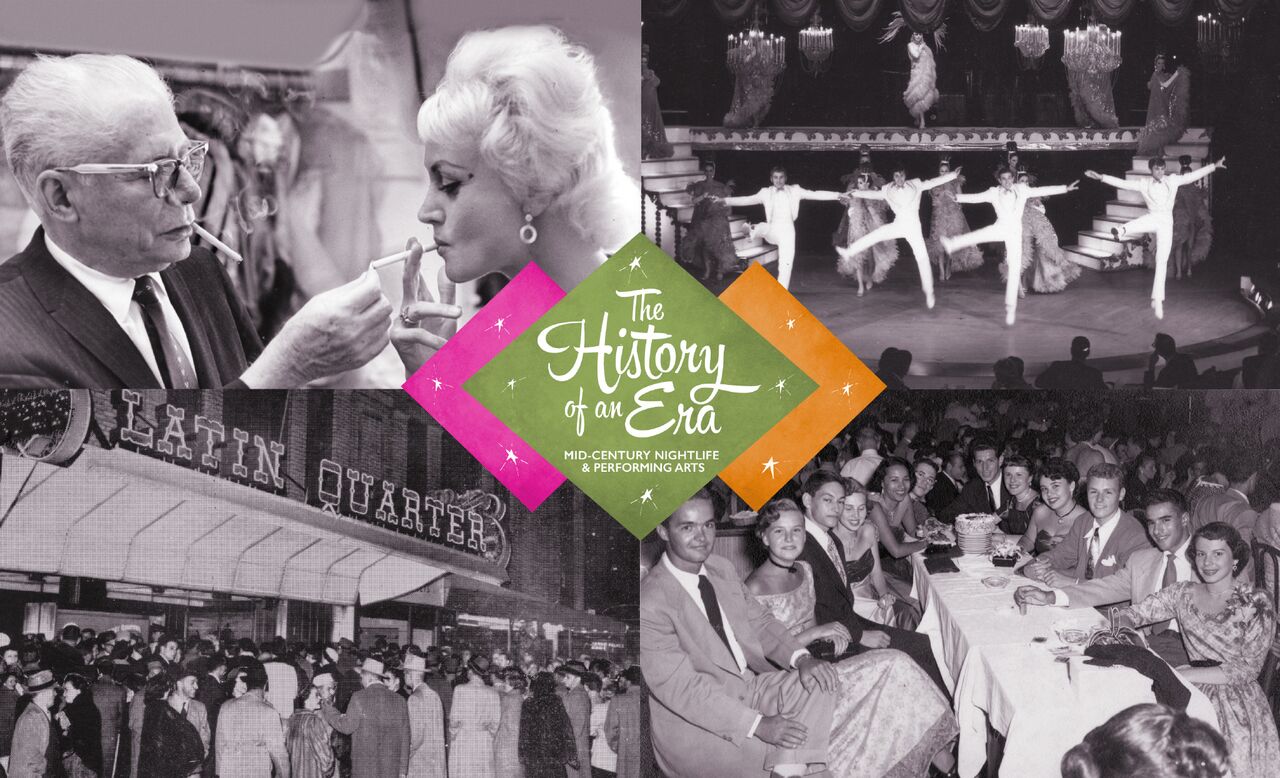

Theatre people all read The Stage paper, which gives all the information for upcoming calls to audition. One day, Betty saw an advertisement. It was for the nightclub producer, Lou Walters.

Lou Walters requires England’s best girl dancers and showgirls for The Latin Quarter, Miami Beach Florida, U.S.A.

REHEARSE

New York, Nov. 25th, 1952. Open Florida Dec. 18th

Salary 30 pounds weekly plus hotel accommodations and roundtrip transportation.

AUDITION

Prince of Wales Theatre, London

Friday, Jan. 25th, 1952 11am

“We could go and still be back for the evening performance,” Betty said. I looked at her, thought for a minute, “Thirty pounds a week, let’s go.”

End of Part I

This article was edited in collaboration with Mollie Fennell Numark and the John Hemmer Archive in 2021. It based on Mollie’s 2017 memoir, Looking Through My Window, a 2018 live presentation at the Shelter Island Public Library in Shelter Island, New York and an oral history conducted at a Latin Quarter performer reunion in 2016. The second installment in this article series is at A Dancer’s Life: Meet Mollie Fennell Numark, Part II

0 Comments