A Dancer’s Life: Meet Lawrence Merritt, Part I

From gin joints to Broadway, dancer, actor, and singer Lawrence Merritt has performed throughout the world over the decades, partnering with some of the greatest stars in the history of entertainment arts. His reflections support his vast experience, all taken with a healthy dose of sharp wit and incredible recall. Here Lawrence breaks down a dancer’s life from the top.

Paper scrapbook page: Black & white composite photographic print, Lawrence Merritt head shots & press imagery, New York, NY, circa late 1950s. Courtesy Lawrence Merritt. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

Okay. Let’s start at the very beginning. Where did you grow up and who were your early artistic influences?

Do you have time? We’ll send out for Chinese food. Well, okay. I was born upstate. A little town and the hospital is now a rooming house in this little village, just south of Saratoga. Saratoga Springs, Saratoga spa, or whatever. The little town is called Ballston Spa because it had mineral waters. But, I grew up out in the country. At the other end of the apple orchard was my cousin. And that was my circle. My Dad would say, “Go play ball.” I finally realized that my father probably never knew how to play ball. He just thought it was the thing you say to your son.

Instead, my recourse was to go into my own little imaginary world, which was quite vivid. I began drawing in the first grade. Bambi and horses and deer for my father, little pictures and movie stars faces and things like that. And I still have some, they were pretty good for first grade. I continued to draw through most of my school years. I wasn’t a brilliant student. I think I was just sort of a shy nerd. When I was in the fourth grade, I took a year of tap dancing and I did a recital in Schenectady in a big theater with a little girl with curls in a pink satin dress. Me with my little satin pants and my little white bolero. Somebody called me a sissy and I went, “Okay, I won’t do that anymore.”

Photochrome postcard: Business District and park, Ballston Spa, NY, circa 1950s. Courtesy John Hemmer Archive. Image subject to copyright laws.

In the 1940’s when I was just a little kid, I’d go to the Ballston Spa movie theater. I would sit and watch Sonja Henie and Carmen Miranda and Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. And I was like five years old. I would be there with my mother and I would just get lost in that world. I believe it’s those cinema experiences that made me eventually decide to become a dancer, the image of Fred Astaire was the one in my head, not somebody in silk tights, tippy toeing around. He was always a masculine image in my mind anyway.

Did you have any mentors in your community who encouraged you along the way?

In high school, I was still really into drawing. I drew the posters for the candy sale in the cafeteria, or the library book sale, or the prom. I was the one who did all the artwork for the yearbook. At one point my English teacher, Mrs. Tilton, who ran the Drama Club, said, “The guy who’s playing the father in the junior play has to drop out. If it doesn’t work out, you’ll have to understand, but we’ll try you out.” I said, “Okay.” So, I played Dad in the Junior Play. Then an assistant gym teacher said, “You know, in Schenectady, they have Schenectady Light Opera and they need singers. You’re in the Glee Cub.” He encouraged me to audition. I went down and I said, “Hello, I’m a tenor.” And they went, “Get over there.” I did Sweethearts, I think. Nobody does that kind of musical anymore.

During my senior year, I was the young male lead in our senior play. I did Music in the Air with Schenectady Light Opera and that same gym teacher told me about a place in Maine. He said, ” It’s kind of like Summer Stock. They do a lot of shows, opera, and musical comedy.” Although, my plan was to work for a year after high school, and then go to New York and attend Parsons for fashion design, I did write the place in Kennebunkport, Maine. The theatre received my letter and I was invited for a visit.

My parents drove me down to Schenectady where I boarded a bus. I was picked up at the other end and was asked to come to this Victorian house on the hill next to their theatre. There they had me sing this la, la, la, la, la, la. The, “Why did you want to come here?” question, to which I replied, “Well, I was in high school plays, the Schenectady Light Opera, I took tap dancing, I’m in the Glee club and I’m going to be a fashion designer and blah, blah, blah.”

Photochrome postcard: Arundel Opera Theatre & Academy of Performing Arts and Related Arts, North St. Kennebunkport, ME, circa 1950s. Courtesy John Hemmer Archive. Image subject to copyright laws.

The next morning, on the way back to the bus they said, “You have a full scholarship, report here on so-and-so date. You will get a $100 for the summer. You’ll get your room and board, and you’ll do whatever you’re going to do.” So, I missed my graduation because I went to Kennebunkport to do Summer Stock and the first day everybody but the older leads, who were usually from New York City or the Robert Shaw Chorale, took a ballet class.

Magazine Ad: Goya & Matteo dance act, unknown publication, circa 1960s. Courtesy John Hemmer Archive. Image subject to copyright laws.

I never pointed my toe. I had some tap. The ballet class choreographer said, “Okay, everybody go back to the theater, learn music, paint sets, whatever. Dancers we’re going to rehearse here on this wooden floor – Oh and Lawrence, you stay too.” The first show was Goethe’s Faust. It’s like, “Okay.” And so I’m doing ballet, peasant stuff, I thought it was going to be a peasant for the rest of my life. But I guess I had a talent for it because I danced in all 10 shows that summer.

This was a seminal experience that changed everything.

Absolutely. Iolanthe – not dancing but singing, Trial by Jury, Call Me Madam, Song of Norway. And every Sunday we would have someone coming to visit us. We had Erik Bruhn and Inge Sand who were part of a mini troop from the Royal Danish Ballet performing for us. The next weekend, we had Carola Goya and Matteo who were ethnic-dancers. They did Spanish and East Indian – famous. Next there would be some incredible pianist, and next, Jean-Léon Destiné and his African dancers and drummers.

I was being exposed to all this and then someone who danced, I think in the chorus, He said, “If you’re interested in this dancing thing, I have an apartment in New York city. I have a roommate, but we have some space, if you want to see if something pans out.” He’s still here in New York City. He ended up being a Spanish and East Indian dancer. He and his partner.

I went home and I said, “Mom, Dad, I want to go to New York, and I want to be on Broadway.” I had not a clue, but it was my innocence and naivety that saved me. If I’d known what it was like, I would have been so chicken. They said, “Well, okay. We’ll support you if that’s what you want.” Once I had their blessing, I picked apples there for a month and saved $100. I got a ride with a local dance teacher who was coming to a convention at the Plaza. And on my 18th birthday, I came to New York. Yeah, that was my big left turn from working for a year to become a fashion designer.

Did your parents ever express concern with you leaving for the ‘big city’ to pursue a life in the performing arts?

I had good parents. They did the best they could do with the instruction sheets that they got. They said, “We’ll support you in whatever, if that’ll make you happy.” And then years later, after my father had passed away, my mother said to me, “That was very hard, to let you go. Your father wanted you to stay home. And I said, ‘No, he’s going to want to go anyway. We really should just let him go.’ So we did.” And I was off. I never looked back.

Paper scrapbook page: Black & white photograph, Lawrence Merritt & Agnes de Mille dancer performing in a Summer Stock production, Cohasset, MA, late 1950s. Courtesy Lawrence Merritt. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

What was your first job in New York City?

Within the first week I was in New York, I sat on a chair with towel on my shoulders in the middle of the living room. And I said to my roommate, ” I bought some peroxide and a comb. Here, I want to be a blonde.” So, we combed it through. It got a little red and I’m like, “Do it again.” So he did it like three times. Well, I did that and my eyebrows and I ended up looking like Lucille Ball. Head bright red hair. That same week I turned 18. Guess what? Selective Service, the draft.

I went out to do that and that was really classic, a lot of men walking around in their t-shirts in their underpants. Somebody putting their hand under your testicles telling you to cough. Then, “Okay, take down your underpants, turn around and bend over.” I thought, “This is so classic. Isn’t this fun? No.” After you go through all that, there’s the one question at the end, “Do you, or have you ever, had homosexual tendencies?” I thought, “Well, why didn’t they just ask me this at the very start?” You’ve got to wonder, right? Then I thought, “I guess everybody knows I’m gay anyway.” I saw my opportunity right there. “Yes.”, I said. I was then sent over to the resident psychiatrist, “Do you realize..,. blah, blah, blah.” I said, “Yeah, okay.”. That’s when we said a mutual “goodbye forever.” I still have my draft card someplace, which looks like the rats have been chewing at it but it still says, “red hair, green eyes”.

I eventually got a job as a typist in the loan department of First National City Bank of New York Incorporated. That’s what it was called then. Now it’s called Citi Corp. And it was on 42nd street between Vanderbilt and Madison, I think. And I worked in the loan department until it was time to go back to Summer Stock the next year.

Paper souvenir photo cover: China D’or nightclub, New York, NY, circa 1950s. Courtesy John Hemmer Archive. Image subject to copyright laws.

In the middle of the summer, however, there was a big upheaval. I still don’t know what it was all about, but we all went, “Yes, we’re leaving.” It felt traumatic at the time, but we all left. A choreographer named Roland Wingfield, approached me. He used to bleach his hair blonde and so did his partner, Carol. They worked with a guy named Michael O’Brien and another dancer, Paula. I don’t remember who the third girl was, but I joined this group. Roland wanted everyone who wasn’t naturally blonde, to bleach, so I became a baby blonde, Afro-Cuban dance crew of all things. Don’t ask. So, there I was stripping my hair again. Because it was naturally brown, I had what looked like black roots three days later. Anyway, we were this Afro-Cuban dance group playing at what I’d say were the better toilets in New York. One was a Chinese restaurant and club on Broadway, between like 48th and 49th, called the China D’or.

The China D’or was upstairs, tables all the way around, a dance floor and a little stage. I think on either side, if I remember correctly, was a door that went backstage. Our crew was made up of boys in white sailor pants rolled up to just below the knee, white shirts, tied, bare midriff, red bandana, and the ever necessary, straw hat with the frayed edges. The girls had white petticoats, white tops, and bandanas too. We were all barefoot. One night some friends came. We were all talking afterward and one of them said, “You know, I’m not sure about you. I really don’t think you’ll go very far because you’re not very good on stage.” I thought, “To hell with you.” I had this inner chip, because, really? I remember thinking, “Don’t ever tell me I can’t do it, because you’ll see, cupcake.”

Photochrome postcard: “Babes in Toyland” performance, Municipal Opera [Muny Opera], Forest Park, St. Louis, MO, 1960. Photograph by Hugo Harper. Courtesy John Hemmer Archive. Image subject to copyright laws.

Was this the point where you stopped working “regular” jobs to pay the rent?

Paper scrapbook page: Lawrence Merritt with partner as adagio act, “The DuBARRYS” publicity photographs & paper Cooks Falls Lodge ad clipping, Cooks Falls, NY, circa late 1950s. Courtesy Lawrence Merritt. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

I still worked at regular jobs – as a waiter and a bartender, but was always performing too. I worked with a Russian woman who worked at Radio City Music Hall. We became an adagio act. We played dives in Brooklyn, and in the middle of snowstorms, three people in the audience. We played the Borscht Belt for one whole summer. I took the gigs I had to in order to eat and anything where I could gain some stage experience, whatever the venue.

I tell people sometimes that I lived Dirty Dancing. People go, “What do you mean?” Well, we were put up and paid a salary at a place called Cooks Falls Lodge in Cooks Falls, New York. Cooks Falls is what they call “over the hump.” That means it’s too far north to be in the chic Monticello, Concord, Grossinger’s, Lake Kiamesha, whatever.

We had our meals there every night. They put us up. We taught Mambo, Cha-cha, and Merengue to Jewish men and women by the pool. Every Saturday, we did one of our numbers, our “Mambo Number Five”, or our Waltz, or our Tango. There was a resident guy who was a comedian MC.

What used to happen was there would be an agent in New York City, because it was drivable, an agent in New York City, who, in his clientele, had a girl singer, maybe a musician, or a dog act, and maybe some other act. They would drive up, and they would play Lake Kiamesha at 8:30, and then they would play Cooks Falls Lodge at 9:00, and some other place at 9:30, and then another place at 10:00. Then, they’d drive in the station wagon back to New York City. After we did our number, I would dance with five ladies, and my partner would dance with five men. We’d go, “Let’s hear it for Shirley. Let’s hear it for Mabel.” Whoever got the most applause won a split of champagne.

As a bartender, I was making decent money, and found it was okay, but I kept thinking, “This is stupid, you came to New York City to dance. You need to get your act together.” I talked to myself a lot like that. “You need to start studying. You need to lose a little weight, and you need to start auditioning.” I started with Matt Mattox, who taught me really any technique I have, and I started auditioning. I got, a job at St. Louis Muny Opera, 10 shows in 10 weeks. It’s the largest outdoor theater in America. I got my equity contract and joined the union. This was 1959. we did Carmen, Babes in Toyland. The first show was Patricia Morison in King and I. Jacques d’Amboise and Allegra Kent in Song of Norway. It was an amazing experience.

Paper scrapbook page: Black & white photograph, Lawrence Merritt (right, foreground) on set with castmates, St. Louis Muny Opera, St. Louis, MO, 1959. Courtesy Lawrence Merritt. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

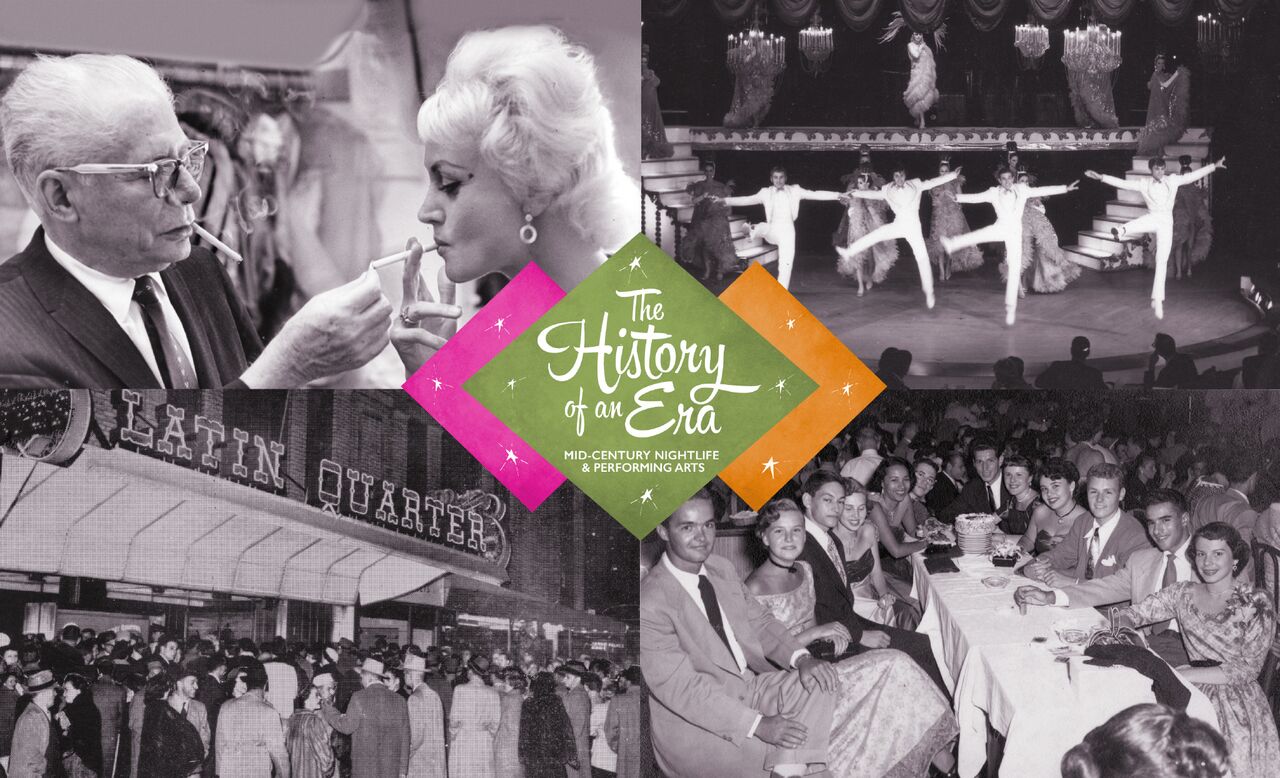

I kept studying. I kept auditioning. I got my first Broadway show in 1962 in No Strings. I should mention, however, that by then, I had danced at the Latin Quarter nightclub. In 1960 I was in a Latin Quarter production for choreographer Ron Lewis, who was a very hard choreographer and also brilliant. The lead dancer was Ron Field. They were partners then. I worked for Ron Lewis several times, including assisting him on Liza Minnelli’s act at the Waldorf-Astoria.

What else do you recall about Lou Walters’ Latin Quarter?

Paper scrapbook detail: Color photograph, Larry Merritt & castmates in costume, backstage, Latin Quarter nightclub, VIVE La FEMME production, New York, NY, 1960. Courtesy Lawrence Merritt. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

It’s a blur, really. I have a good memory though, and they were fantastic people. Ron Field was a great dancer. Ron Lewis was an extraordinary choreographer. The girls in that show kicked ass. Ron Lewis choreographed the Can-Can. We did one number with Gloria LeRoy called My Lean Baby, which was a jazz number. We wore black pants, bright emerald green cummerbunds, white shirts, bow ties, and emerald green boleros, like waiter jackets – but, we did it in red light. A red spot. When you put a red spot on emerald green, it turns black. The cummerbund and the jackets, we looked like we were all in black. The pants were black. Then, when Gloria LeRoy came out, and she did a famous song that Dolores Gray did in a movie, I think, called It’s Always Fair Weather, called, Thanks a Lot, But No Thanks. [singing]. She blew up all these male dancers that came on, sending them down chutes and things. There were four boy dancers with her. It was myself, Ron Field, my best friend at the time and another guy. I can’t remember his name. He was Canadian. You know, you lose people along the way. They either don’t stay in the business, or you don’t know what happened. You wonder sometimes, because you meet so many people that you brush against, you know?

Anyway, I remember that New Year’s Eve at the Latin Quarter. We did the opening show at 8:00, or 9:00, for the dinner crowd. Then, we were going to do a special late-night show, so we got into our opening costumes and went upstairs to the roof, which was right near Tickets, but it was only three stories back then. You went in the front entrance on 48th Street, and on 47th Street was Castro Convertibles, like Jennifer Sofas. It was on the first floor, and up above was the back end of the Latin Quarter. Just before New Year’s, we went up to the roof. We all are costumed, and we all watched the millions of people, and of course the ball drop. Then, we went downstairs and did the midnight show.

What about backstage? I hear different descriptions depending on the time period a performer was there.

Paper scrapbook page: Silver gelatin black & white photograph, Lawrence Merritt in costume, backstage, Latin Quarter nightclub, VIVE La FEMME production, New York, NY, 1960. Courtesy Lawrence Merritt. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

The girls’ dressing room was upstairs. The boys were in the back in some hole. There was a little balcony. You could get out there and peek down at the audience. The spotlight was up in the back, upstairs. The girls were on one side, and you could go around to the walkway on the other side, and there were two slides held up to the ceiling, electrically, with a metal foot petal, like a brace. When this one number was finished, we went out and grabbed the stuff, and the curtain came down, the slides came down. You hear … [singing] We helped the girls come off the slides.

There was an ice-skating rink at the Latin Quarter that lived in the wings. You know how big the Latin Quarter stage was? Smaller than it looks in pictures, but it had this passerelle, this wide passerelle. In the club – the house, there were tables right here [points close], with the passerelle right here [motions again], and then the stage was right there [motions a short distance again]. So, you were looking up at the dancers. The passerelle had lights underneath it. It was heavy plexiglass, so it could go red, or pink, or blue.

Anyway, in the wings it was this huge thing on wheels. It was probably seven or eight feet, by seven or eight feet. It came out of the wings on wheels for ice shows. This particular act was a muscle guy, named Tasha, and his wife was Ruth. She was absolutely spectacular, gorgeous-looking woman, with bright red hair. I’ve seen her in recent years. She lives up on 54th Street, walking her dog. Her husband passed some time ago. I think they ran the rink at Radio City Music Hall for a long time. Anyhow, the last night that Ron Field was there, we were in our gold lamé with white sparkles costumes. The girls were all in gold, with gold caps. Ron Field got up on the rink and skated around on his last night. I did the same thing, I think I left a couple weeks after him.

Paper program detail: Latin Quarter paper program, VIVE La FEMME production, Latin Quarter nightclub, New York, NY, 1960. Courtesy John Hemmer Archive, Image subject to copyright laws.

I tell you though, the girls in that show, I mean, one went on to be in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. Another went on and was in How to Succeed in Business on Broadway. Amazing dancers, because Ron’s choreography was so strong.

Okay, let me make sure that I’m getting some of this in chronological order, here. ’60, you were at the Latin Quarter, correct?

Paper scrapbook page: Playbill cover, No Strings, 54th Street Theatre, New York, NY, 1962. Courtesy Lawrence Merritt. Image subject to copyright laws. Please do not appropriate.

Yup, and ’61 was my first Broadway experience in No Strings [featuring Diahann Carroll], but just before that, I did La Parisienne with Matt Mattox at Dunes Hotel, in Vegas. Matt Mattox choreographed, Michel Legrand did the music. We rehearsed in Paris for a month, my first time, and he asked for me. The rest of the four boys were from LA. That was nice. I came back, and I did No Strings.

At the end of ’62, I don’t know why I left, but six months was my due date. I’d left and I went into Ron Field’s first Broadway show, which was Nowhere to Go But Up, which was directed by Sidney Lumet. His assistant was Michael Bennett. The person who wrote the book and the lyrics was James Lipton. [Starting at the Shubert Theatre in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Then onto the Winter Garden Theatre in New York City]. There were 8 boys and 16 girls, who were all dancer singers. There were no singers in the show. Dorothy Loudon, Tom Bosley, Martin Balsam. The young male lead was Bert Convy, who had done Cabaret, and then graduated to TV game show fame. The ingénue, out of town, or in New York City, before we went out of town, was Louise Lasser. She was replaced by Mary Ann Mobley and Mary was just sweet as sugar. I never did know that Mel Brooks came in to doctor the show. I guess that happened.

This all took place during the Cuban Missile Crisis. We thought we were all going to have to walk back to New York City, which we would find leveled and in rubble, and try to go through our things in our apartment. That was pretty scary.

End of Part I

The above interview with Lawrence Merritt was conducted in 2015. It was edited with Merritt in 2020.

See https://www.johnhemmerarchive.org/a-dancers-life-meet-lawrence-merritt-part-ii/ for the second installment in this article series

To read Part III, the final installment in this series, https://www.johnhemmerarchive.org/a-dancers-life-meet-lawrence-merritt-part-iii/

Watch Lawrence Merritt’s oral history video here:

Meet the Entertainers: Lawrence Merritt from KirstenStudio on Vimeo.

0 Comments